Stepney Children’s Pageant, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 4th-20th May 1909 – The first of its kind

*Guest post by Ellie Reid, Oxfordshire History Centre*

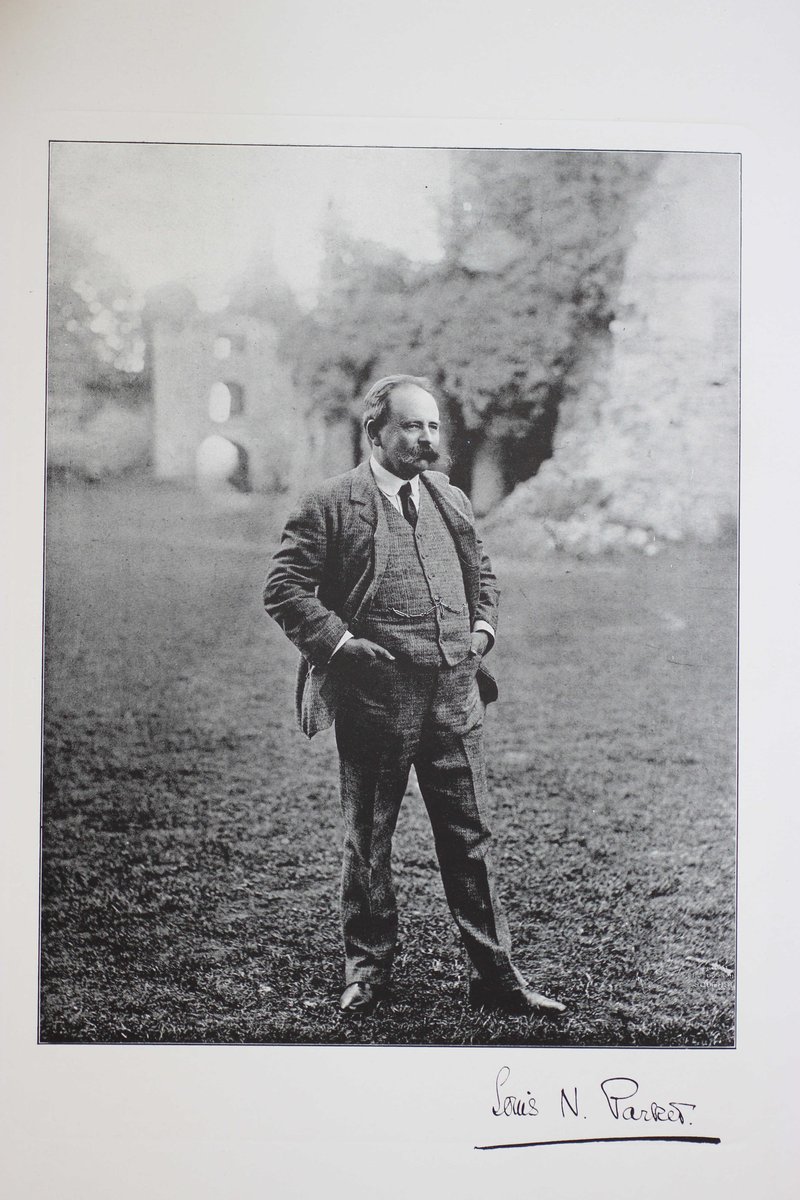

In 1909, Pageant Master Louis Napoleon Parker, ‘the inventor of the modern pageant’, announced his intention to withdraw from large-scale pageant making after the York Historical Pageant in July. The craze for pageants, originated by his 1905 Sherborne Historical Pageant, led to such a proliferation of similar events that it became fashionable to disparage the form. Even Parker admitted that pageantry had been overdone. Nevertheless, he said he was proud to have found a vehicle for the ‘right kind of patriotism’ that ‘had brought all classes together to work and to play in perfect harmony and goodwill without distinction of creed, politics or position’. Parker, a former schoolmaster, believed that pageants could be ‘a great educational force, teaching the young by living example.’ It was this idea that provided a new direction for historical pageants. Children were not just going to be spectators or play the parts of children from the past, they were to perform the adult roles in a move that created ‘children’s pageants’ - the first of which was staged in May 1909 at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the East End of London.

The Whitechapel Art Gallery, Whitechapel High Street, Tower Hamlets, London (closed for refurbishment), 28 November 2005. Photographer: Fin Fahey. CC Licence.

Cecil P. Goodden, The Story of the Sherborne Pageant (Sherborne, 1906). Dorset History Centre: 791.624

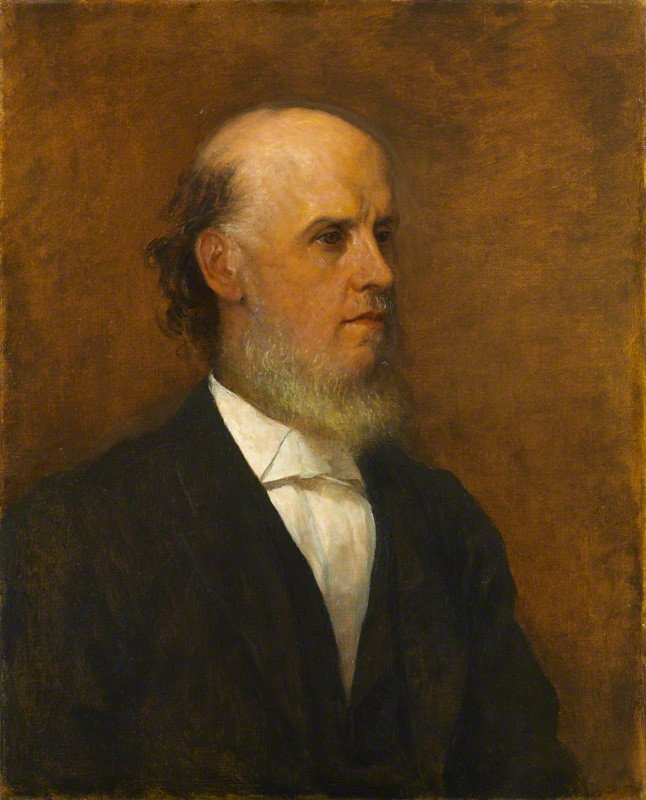

The educational potential of historical pageants had caught the attention of social reformer Canon Samuel Barnett, who championed initiatives to provide educational opportunities for all. His involvement in non-denominational projects in Whitechapel included the founding of the university settlement, Toynbee Hall in 1884, and the opening in 1901 of Whitechapel Art Gallery, a venue for free public art exhibitions. In 1908, it was proposed that a series of historical tableaux illustrating important events in the story of London be staged in the art gallery. Parker’s advice was sought and it was consequently decided to dispense with static tableaux in favour of dramatic episodes. Such a pageant would have greater appeal for spectators, but had the disadvantage or requiring rather more space. This gave rise to the suggestion that because adults ‘would have occupied too much room on the necessarily small stage of the Art Gallery,’ children could be used as the actors in a novel and more educationally beneficial form of pageant – the children would be given the opportunity of “living” the lives of characters they had read about.

Samuel Augustus Barnett by George Frederic Watts. NPG 2893, © National Portrait Gallery, London. CC License.

At the beginning of the autumn term of 1908, Parker addressed an audience at Toynbee Hall on the subject of historical pageants, and Barnett announced that with Parker’s assistance, it was hoped to stage a pageant involving East-End schools at the Whitechapel Art Gallery the following spring. The East End News later reported Barnett’s view that: ‘The object of the Children’s Pageant is to give the people of East London an interest in the past in which the present has its roots. Such interest is likely to enlarge their minds, to give a better understanding of citizenship, and a more stable basis of patriotism’.

Head teachers of Stepney and Whitechapel schools were among the eighty citizens who attended a meeting in November at which the various committees required to stage the pageant were formed. Barnett regarded teachers as key members of their local community, so largely for their benefit, in preparation for the pageant, an explanatory course of five lectures was arranged at Toynbee Hall by the University of London Extension Board. The teaching of history in schools was not then compulsory but was promoted by Board of Education guidance. Teaching methods were not prescribed so teachers were free to adopt approaches most suited to the local circumstances. The proposed pageant clearly appealed as the lectures drew large audiences. Chairing the first lecture, the newspaper proprietor Harry Lawson, Mayor of Stepney, and himself a history graduate, declared that ‘the East-end was giving an important lead to the rest of London in organizing such a pageant’ and that ‘it would be the means of imparting instruction in history in a most attractive manner, and would bring home to the young a sense of the magnificence of their heritage’. Chairing the second lecture, Reverend George Hanks, Rector of Whitechapel, said that the study of history was ‘nowhere more valuable than in the East-end, where its proper teaching might make the children proud not only of being English and Londoners, but of being also East-enders’.

The pageant was able to draw on the influential and talented group of individuals who supported the educational objectives of Toynbee Hall and Whitechapel Art Gallery. Parker provided assistance and advice to the project, and personally supervised the final fortnight of rehearsals though declined the title of Pageant Master. Canon Barnett chaired the Pageant Committee, while Charles Aitken, director of the gallery, took responsibility for much of the general organisation as pageant director. Writer and publisher of children’s literature, Frederick J. Harvey Darton, took on the role of stage manager. Various authors contributed to the pageant’s libretto, Darton amongst them. The other writers were: ‘Cockney school’ novelist, William Pett Ridge; Kenneth Vickers, an Oxford graduate, lecturer in London history for London County Council and tutor to the University of London joint committee for adult education tutorial classes; George K. Menzies of the Royal Society of Arts, a contributor to Punch, and Charles Harrison Townsend, architect of the Whitechapel Art Gallery. The music committee was chaired by professional musician and suffragist Rosabel Watson; a graduate of the Guildhall School of Music, whose philanthropic work included organising concerts at Toynbee Hall. Watson provided her all-female professional “Aeolian Orchestra” to perform the incidental music which was composed especially by Gustav von Holst.

In 1909, Holst, who was yet to achieve the recognition that followed the success of his orchestral suite The Planets, earned his living as a teacher. Holding teaching positions at St Paul’s Girls’ School, Hammersmith and Morley College for Working Men and Women, Southwark, he taught both adults and children. He undertook the Stepney pageant project on the condition that he composed the score in its entirety. His incidental music comprised the Overture, the Opening Chorus, the Choral Ode and an interlude entitled ‘The Blind Beggar’s Daughter of Bethnal Green’, the latter being based on the legend told in the old English ballad of the same name. Government education policy at that time encouraged the teaching of traditional song and dance in schools, a topic embraced by Holst who had an interest in the English folk song movement through his friendship with Ralph Vaughan Williams. Since the pageant also included Morris dancing, the ‘Stepney Children’s Pageant Book of Words’ acknowledged that ‘certain songs and dances are founded on English traditional melodies’ and were used by permission of the song collectors and publishers.

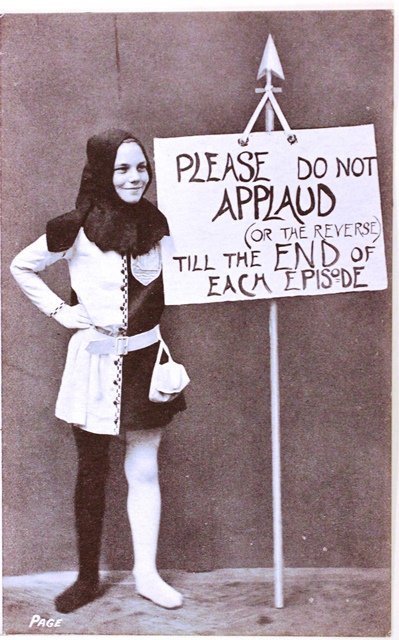

A Page, and William the Conqueror with soldiers

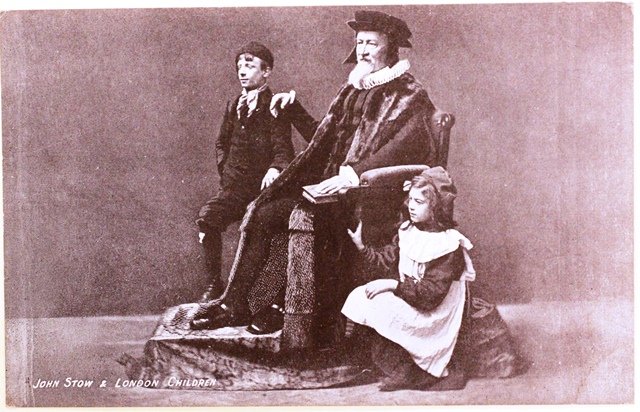

The pageant portrayed a mix of local and national events, written with the usual artistic licence. The episodes were presented by the character ‘Old Stow’, played by the only adult in the cast. His role was to show two Cockney children that, contrary to their preconceptions, the history of London was not as dull as it seemed. The choice of narrator and the design of his costume drew on the familiarity of some of the children at least with the surviving monument to the London chronicler John Stow in the nearby City of London Church of St Andrew Undershaft.

John Stow and London Children

Six hundred children from twenty one local schools took part in the pageant. It was performed in its entirety on two afternoons and eleven weekday evenings, in a schedule that, at request of the office of the Chief Rabbi, avoided the Jewish Sabbath and therefore enabled members of the Jewish community to participate. The children were organised in two alternating shifts, (a) and (b):

Opening Chorus (sung by Dempsey Street School)

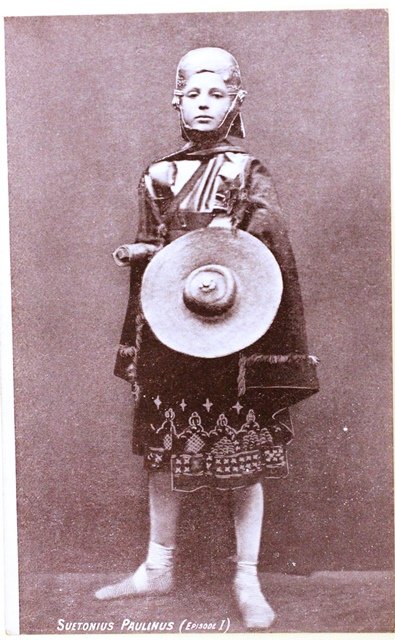

Episode 1. AD 61 The death of Boadicea (a) Deal Street School and (b) Settles Street School

Episode 2. AD 1066 William the Conqueror’s Charter (a) Old Castle Street School and (b) The Davenant School

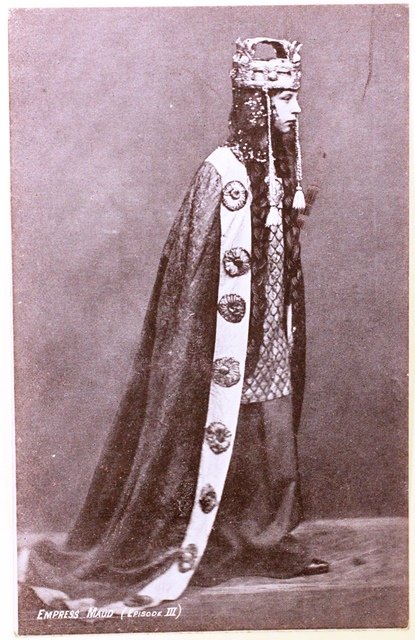

Episode 3. AD 1141 The rejection of Empress Maud (a) Broad Street School and (b) Lower Chapman Street School

Morris Dance (a) Berner Street School (b) Brewhouse Lane School

Episode 4. AD 1191.The Granting of the Commune (a) Commercial Street School (boys) and Hanbury Street School (girls) (b) Chicksand Street School (boys and girls)

Interlude: The Blind Beggar’s Daughter of Bethnal Green – performed by children of Jews’ Free School

Episode 5. AD 1381 The King’s meeting with Wat Tyler at Mile End (a) Stepney Jewish School and (b) Stepney Play Centre

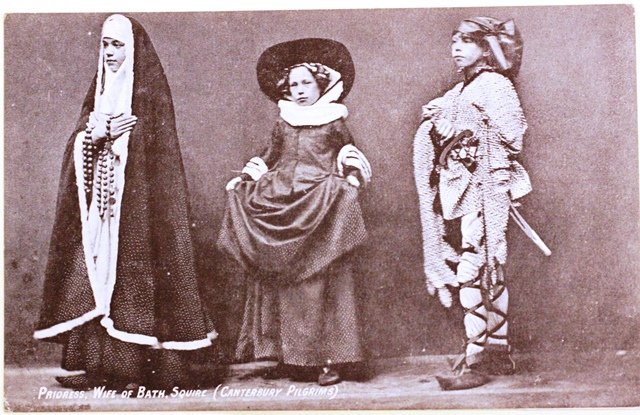

Interlude: Canterbury Pilgrims (a) Red Coat School and Green Coat School and (b) St Paul’s National School and St Thomas’s Colet School.

Episode 6: AD 1588 The Departure of the Stepney Men to fight the Armada (a) Stepney Central Girls’ School and Old Montague Street School (boys)

Choral Ode sung by Dempsey Street School as the performers made a March Past.

Richard II (Episode V), and Suetonius Paulinus (Episode I)

Two complete casts and one set of understudies were chosen in order to involve as many schools as possible, but since only one set of costumes could be afforded, performers in both shifts and their understudies had to be the same size. Female roles were under-represented, the Toynbee Record acknowledged, as ‘history in the period covered did not allow much scope for the movements of women’. The organisers were reported to have attempted to address the imbalance ‘by allotting the dances to girls and allowing them to take ecclesiastical and similar parts in which long robes were worn'. Parker’s ideas on pageantry included a belief in the educational value and possible economic benefit of making costumes, armour and props locally. This view coincided with the Gallery’s aim to promote local handicrafts. Members of the Dress Committee produced historically correct costume designs and the children spent the winter sewing their costumes. Stepney Jewish School made weapons while the Sir John Cass Institute and the Craft School at Stepney Green, made spears, crowns and other props.

One difficulty facing the pageant organisers, however, was funding. While the Book of Words recorded the generosity of donors such as the West End theatrical costumiers Clarkson’s, supplier of the principal wigs, and other firms who provided materials and services, there were still expenses to be covered. Although the trustees of the gallery guaranteed the expenses of the pageant up to a certain amount, the constitution of the Gallery prohibited making a charge for tickets to the pageant to address the shortfall. On May 11th 1909, an appeal by Barnett and Lawson appeared in The Times seeking donations to help defray the costs of the event. The gallery accounts show that the pageant cost just over £400 to stage, £196 of which was covered by special donations. £38 was made on the sale of books of words, programmes and photographs and £9 received in collecting boxes leaving a shortfall of £157 - not an unexpected result.

Ticketing the pageant was necessary due to the limitations of the space available. The twenty-five foot wide stage took up part of the ground floor of the main gallery with small adjacent rooms being used as the wings. The upper floor was reserved for the performers and the basement used for dressing and waiting rooms. Up to 600 spectators could be accommodated with the front rows were reserved for children, and reports indicate that gallery was filled to capacity.

Empress Maud (Episode III)

In its review of the first performance, The Times described the large audience, chiefly of performers’ families, who filling the gallery ‘were carried in the twinkling of an eye from the drab and complex commonplaces of the twentieth century to the picturesque simplicity of the first.’ The newspaper noted that while it couldn’t be determined whether the pageant would succeed in making the children feel a proper pride in being citizens of London, they certainly entered into the spirit of the thing, and that ‘the whole effect, particularly when the children marched in procession past Queen Elizabeth and her Court, was a glowing and moving spectacle’. The East London Observer commented: ‘It is not a show, it is real life, and the children live it with the overwhelming realism of childhood. From the first note of the rousing opening chorus to the last march, rang the music of the glory of duty to the city and duty to the state’.

One spectator was the actor J. Harry Irvine, pageant master of the 1908 Chelsea pageant. In a letter to Campbell Ross, pageant secretary at Whitechapel, Irvine thanked Ross for arranging his tickets and offered his own observations on the pageant ‘as I am in the pageant line myself’. He itemised what he admitted were ‘very plain-spoken criticisms’ about the performance. Although he found a high level of interest was maintained throughout, he thought a simpler script would have been more successful and that the ‘main fault’ was the ‘undue proportion of speech to action’. While Irvine made these and other criticisms, it seems he would have liked to have contributed to the event – regarding costumes, he said ‘we could have helped you a good deal’. Irvine did, however, declare that the interlude ‘The Blind Beggar’s Daughter of Bethnal Green’, written by George Menzies and performed by children from the Jews’ Free School, was ‘unquestionably the best feature of the evening’.

The Jewish Chronicle celebrated the significant contribution of the Jewish community to the event:

‘The Jewish children played several leading parts in the various episodes. They came from Deal Street, Settles Street, Old Castle Street and Berner Street (Morris Dances), Myrdle Street, Old Montague Street and Stepney Jewish. We had too, a Jewish Queen Elizabeth – a live Jewish Queen, beshrew me! The greater number of costumes and properties have, I learn, been “evolved” at the Stepney Jewish School, much ingenuity having been shown in their manufacture. One of the most energetic workers in the property department has been Mr. Arthur Harris (also of Stepney School), who has fashioned such trifles as swords, sandals and ancient armour from the most commonplace materials – and fashioned them excellently, too. Other Jewish schools were responsible for the making of the dresses, while the Jewish element was well represented on the various Committees of the Pageant.’

The report also described the pageant as challenging the prevailing view of East End children:

‘The scene on the opening night was one of animation and colour, and surely the brightest spot of colour was the scarlet-robed Mayor of Stepney, who seemed to become a child in spirit once again as the story of the Pageant unfolded itself. Visitors from the other end of town were obviously astounded. Could these be the children from sordid Whitechapel, the home of “cramped sunless lives”? They fairly gasped at the brightness, the vivacity, and the manifest artistic sense of the participators’.

Prioress, Wife of Bath, with squire and Canterbury Pilgrims

The reputation of Barnett and the Whitechapel Art Gallery was such that the pageant even succeeded in gaining royal patronage. On 14th May, the royal children, 12 year-old Princess Mary and 9 year-old Prince Henry of Wales, accompanied by some of their friends, a governess and a tutor attended a special royal matinee. Prince Henry was presented with ‘a pair of splendid swords, of Roman model, with scabbards of hammered copper and hilts of bright steel’ and a belt that ‘boasted a buckle that bore in enamel a picture of an ancient ship in full sail, with the Red Cross of St. George emblazoned on the canvas’ that had been worked by the pupils of the Sir John Cass Technical Institute and by the boys of Stepney Jewish School. Gifts for Princess Mary included a Book of Words in an especially embroidered cover worked by girls of Myrdle Street School and an album of photographs of the event. The Mayor of Stepney, Harry Lawson said that the pageant had been great delight to the East End and if 'the art of pageantry was to become a permanent institution it must rest on the shoulders of the children. It would be impossible for the cities and boroughs of England to reproduce the pageants which had been seen in the last few years, but it would always be possible for the children. For them, a pageant would provide a background to English history and there could be no better means of inculcating patriotism.’ Canon Barnett joined Lawson’s words of appreciation for all who had helped with the pageant, ‘emphasizing in particular the labour of the teachers, who, behind the scenes, were keeping kings and queens quiet, mending their dresses, and putting on their paint.’

To capitalise on the success of the pageant and the interest it had generated, the trustees of art gallery decided to follow the Stepney Children’s Pageant with a Historical and Pageant Exhibition of pictorial and applied art to further stimulate the interest of local people in both local and national history. The organisers were able to draw on distinguished individuals for expertise and the loan of items. Original portraits and paintings of historical subjects, and examples of genuine Tudor and Stuart costumes, weapons and armour were exhibited along with banners, chariots, costumes, weapons and other props loaned by pageant towns and cities from Glasgow to Dover, including Boadicea’s chariot from Louis Parker’s Colchester Pageant of June 1909. To maximize the educational benefits of the exhibition, large numbers of local school children were taken round the exhibition by the Director, teachers and voluntary guides, before the gallery opened to the public each morning. For adults, a series of five Saturday evening lectures on the history of London were given by Kenneth Vickers as part of the University Extension Scheme of the London University. The exhibition ran from 20th October- 5th December 1909, a week longer than originally planned – the extended date causing one Colchester resident Miss Ord to write and ask when she might get her ‘carved sword’ back.

Provided by Ellie Reid.

The Stepney Children’s pageant was a notable event in the history of historical pageants. Samuel Barnett, Louis Napoleon Parker, members of the local community, and a host of influential supporters created a novel form of pageant to specifically fulfil their educational aims. Education remained central to most of the historical pageants that followed, but Parker still continued to retreat from historical pageantry and, in his 1928 autobiography, ranted sternly against the ways the format had developed in the 1910s and 1920s especially. But others saw the potential of children's pageants, and more followed. Little more than a month after Stepney Children’s Pageant, a ‘Children’s Pageant of the history of Kent and Tonbridge Castle’ was held during the week of Tonbridge’s Fire Brigades’ tournament. On 2nd July, the Kent & Sussex Courier reported on the ‘Gargantuan task which Mr. J.F. Ash, the registrar and librarian at Tonbridge School, set himself when about five weeks ago, he introduced the idea of a children’s pageant’. The pageant was to be ‘on the lines of the great pageants which have been produced under the direct of Mr Louis Parker and others.’ Ash wrote the Book of Words himself and the resulting pageant, which comprised nine episodes and a grand tableau with a Chinese lantern procession, was enacted by 540 local elementary school children. However, the precedent of the Stepney children’s pageant was seemingly unacknowledged as a local newspaper report declared: 'Parenthetically, it is interesting to note that this is the first Children’s pageant of any consequence to be performed in England, and Mr Ash may be warmly congratulated upon the splendid success of his unique enterprise.’ Already, through the creation of another historical pageant, Stepney's own had quickly been forgotten.

All photographs of performers from - Stepney Children's Pageant Photographs (1909), Louis Napoleon Parker Papers, Box 25, Folder 4, Series VI: Photographs (sub folder 2), Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.